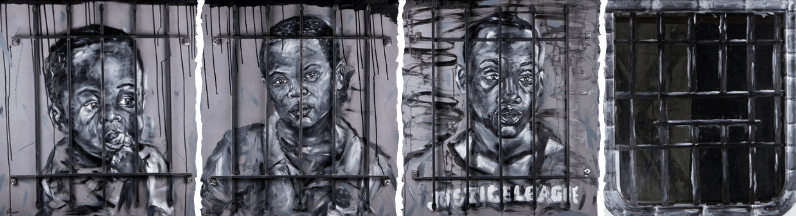

“If the justice system does not change incarceration will continue to be as arbitrary as a game of eeny, meeny, miny, mo, with black kids and black men hoping to avoid being ‘IT.’”

Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo is the title of this series of paintings by Nashville native Omari Booker, a visual artist who has spent a lot of time thinking about race and mass incarceration in America. He explains that many people may not realize the familiar children’s rhyme the title is based on (eeny, meeny, miny, mo, catch a tiger by the toe, if he hollers let him go…) has racially charged origins: traditional 19th– and early 20th-century American versions use the word n*gger instead of tiger. Booker’s art shows hauntingly how America’s Cradle to Prison Pipeline™ is catching Black boys. He writes:

“I have focused on three children who I met in North Nashville as references for the three paintings… The 37208 zip code which covers the North Nashville area is the most incarcerated zip code in the country. I met the youngest boy at the Garden Brunch Restaurant, the next at Hadley Park Community Center, and the oldest comes into the gallery where I work and sells candy from time to time.

“It is important to be confronted with the imagery of a child behind bars. The cradle to prison pipeline is not an abstract idea. It is an intentional, efficient system that successfully targets black boys, and they are selected arbitrarily and consistently. Mo, the last piece in the installation, is a mirror. The mirror is intended to elicit change by way of proximity. Seeing oneself behind bars is intended to personalize the problem that is so often seen as a ‘them’ issue. Prisons are tucked in the corners of states, and in the background of society. Many do not feel affected by the system because it has not directly touched them. I hope the mirror is a reminder that anyone could be Mo. Anyone could be behind those bars.”

Booker knows this fact all too well. A gifted artist since high school, he studied at Belmont University, Middle Tennessee State University, and Tennessee State University, where he earned a B.S. in Graphic Design. But his creativity and talent became a tool for survival in prison after he was given a 15-year sentence for a drug possession charge. In prison, he says, art transformed into a necessity: “I began my journey of connecting with freedom and my own humanity through art….Drawing portraits for officers and inmates and writing about my experiences became therapeutic and cathartic. The difficulty never subsided, but I was keenly aware of the fact that I had found a tangible link to freedom regardless of my circumstances.” In the years since his release Booker has never stopped his prolific creativity. Freedom through art is his guiding philosophy. He channels it into his work teaching art to young Black boys at risk of entering the cradle to prison pipeline with whom he shares his experiences in hopes of helping them avoid getting trapped by the criminal justice system.

The Eeny, Meeny, Miny, Mo series is now on display at the Children’s Defense Fund’s national headquarters and is a searing daily reminder of how many children are not free but caged in America. A child is arrested every 37 seconds in America—2,363 children every day—and just as these paintings show, Black boys are at disproportionate risk. Black children are approximately two-and-a-half times more likely to be arrested than White children and Black youths are nine times more likely than White youths to receive an adult prison sentence. The faces of these beautiful boys represent the thousands of other real children behind these statistics trapped in America’s cradle to prison pipeline crisis every day and often unable to see a way out.

There is some good news. Thanks to the bipartisan leadership of Senators Charles Grassley (R-IA) and Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Representatives Jason Lewis (R-MN) and Bobby Scott (D-VA) and strong support in the youth justice community, the Juvenile Justice Reform Act of 2018 passed in December. This law reauthorizes and strengthens the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act which hadn’t been reauthorized since it expired in 2007. It improves core protections requiring states to address racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system, do more to keep children out of adult jails and lock-ups, and provide alternatives to detention for status offenders (children charged with offenses that are not crimes if committed by adults like truancy or running away from home).

The Juvenile Justice Reform Act also enhances evidence-based and trauma-informed practices in juvenile facilities, requires states to maintain data on restraints and isolation and describe the strategies they are using to reduce isolation, and requires federal training and technical assistance to support those goals. And also in December, the First Step Act was enacted which went further and prohibited all federal facilities from using solitary confinement as punishment for youths, with only a limited exception. Hopefully states will now follow suit and end the practice of placing youths in solitary in state and local detention centers, jails, and prisons, where most of them are confined.

While these are all critically important steps forward, much more action is needed to promote prevention, divert children from the justice system, reduce institutionalization, stop all solitary confinement, and engage youths, families and communities in the work to dismantle the cradle to prison pipeline. Every day that we don’t make these changes millions of children and youths across the country remain at risk. Ending up in prison should not be a matter of losing a game of chance with the odds stacked against you. I urge you to imagine the children in your own life in these paintings and remember: Anyone could be Mo.